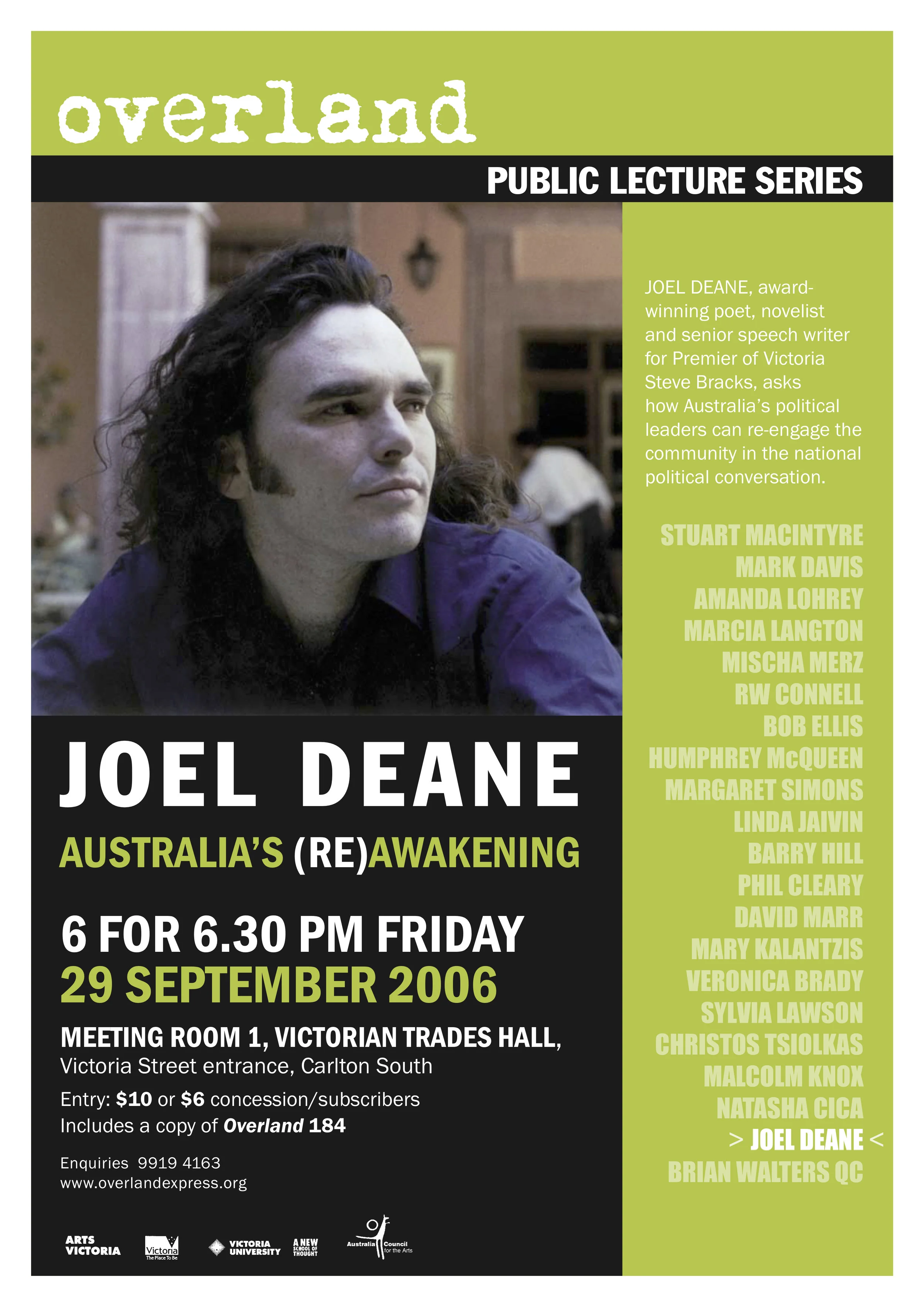

From the archive: Australia’s (Re)awakening

Delivered on 26 September 2006 as part of the Overland Public Lecture Series.

First published in Overland 184.

Australia’s former Prime Minister, John Howard, is many things, but he is not the alpha and omega of cricket tragics. That honorarium would be, in my view, best bestowed upon C.L.R. James; the late and great Trinidadian essayist, author, Marxist, and post-colonial activist, who, in 1963, published what many fellow tragics—not to mention former Australian Test captain Richie Benaud—have come to consider the masterwork of cricket literature: Beyond a Boundary.[i] What makes Beyond a Boundary such a classic is its ability to transcend sport, culture, politics, race, and colonialism—an all-round performance of Sir Garfield Sobers-like proportions when compared to the hit-and-giggle offerings of most sporting tomes.

Here, for example, is James—who died in England on the day Alan Border’s Australians were playing a warm-up match against Somerset at the beginning of their curmudgeonly, and ultimately victorious, 1989 campaign to win back the Ashes—explaining how the way people play sport is an expression of their social, economic, and racial backgrounds:

‘I haven’t the slightest doubt that the clash of race, caste and class did not retard but stimulated West Indian cricket. I am equally certain that, in those years, social and political passions, denied normal outlets, expressed themselves so fiercely in cricket (and other games) precisely because they were games. … The British tradition soaked deep into me was that when you entered the sporting arena you left behind you the sordid compromises of everyday existence. Yet for us to do that we would have had to divest ourselves of our skins. … Thus the cricket field was a stage on which selected individuals played representative roles which were charged with social significance.’[ii]

In other words, sporting cultures reflect national cultures, as well as the times and mores of the individual competitors and the communities those individuals represent. Consequently, Australians play cricket differently to Englishmen, who play differently to West Indians, who play differently to Indians, who play differently to Pakistanis, who play differently to New Zealanders, who play differently to South Africans, who play differently to Sri Lankans—leaving each competing nation’s tragics free to applaud their flannelled fools and abhor their opponents’ poor cricketing character. Why the abhorring? Because the way each nation plays and perceives sport reflects its national culture.

Much the same could be said of democracy.

Like it or not, a nation’s political culture is a reflection of its national culture. As such, no two political cultures—particularly democratic ones—are the same, because each democracy cannot help but reflect past and present social and economic circumstances. Which begs the question: What kind of democracy has Australia’s social and economic circumstances, past and present, begotten? Is our democracy, to put it in terms a cricket tragic could fathom, more like Sir Donald Bradman’s 1948 Invincibles, who charmed and defeated the Old Enemy, or Alan Border’s 1989 Incorrigibles, who sledged and bludgeoned?

If I had to choose, I would say our national democracy is currently closer to Border than Bradman. Why? Because our national leaders have spent much of the past decade either inflaming or ignoring matters of national importance, depending on political expediency, and the majority of the electorate has not seemed to care. There has, in short, been a disconnection between the individuals elected to Federal Parliament and the communities they are supposed to represent. Without that connection, politics cannot be, as James said, ‘charged with social significance’ and becomes, instead, increasingly hollow and remote to all but the most tragic of political tragics, like a dead Test played in an empty stadium.

The disconnection of democracy, the loss of social significance, was, I suspect, very much to the Howard Government’s liking. But was this disconnection solely of the Howard Government’s making?

Many of the former opponents of the Howard Government would probably answer with a resounding ‘yes’—citing instances such as the stymieing of the Republican debate, the shutting down of the movement for Reconciliation, the neutering of Non-Government Organisations that have an advocacy role[iii], innumerable prevarications over climate change, the scapegoating of Australia’s Islamic community since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and the subsequent riots in and around Cronulla, but I am not convinced.

And what of the Rudd Government? Will Federal Labor reconnect the machinery of democracy with the men and women it should represent? The early signs, such as the advent of community Cabinet meetings and Kevin Rudd’s historic apology to Indigenous Australians, are good, but it’s still too early to say. Only time and hindsight reveal a Government’s true nature.

Think of it this way. Elections are the democratic equivalent of an arranged marriage, with the groom (or bride, if you prefer) that is the electorate having to, in effect choose between two prospective partners—Labor or Liberal-National, progressive or conservative, Kevin or John. Some members of the electorate like neither option and either choose to not vote or scrawl obscenities on their ballot paper. Others are passionate about one or the other partner. A significant number, even before they’ve jumped the broom, have their eye on an extramarital roll in the hay with the Greens or Family First or the Democrats or a swinging independent. Most, though, will pragmatically choose the suitor they find least objectionable.

Once the confetti clears and the marriage is formally arranged there is, usually, a honeymoon of sorts as the electorate enjoys the buzz of sharing the democratic bunk bed (lower bunk for the House of Reps, top bunk for the Senate) with a new executive body. As with any marriage, though, it takes longer than a weekend in Surfer’s Paradise to get to know a new Government, because Governments are, like people, complex, multifaceted and contradictory in ways that only human beings and the institutions they construct can be.

Governments are, after all, a lot like ant colonies. The Prime Minister may well be, if you’ll excuse my illustrative cross-dressing, Queen, but the hard yakka of governing is carried out by everyone else—from the soldier ants of the public servants to the worker ants of the broader community. A Government’s success and failure, therefore, is not wholly within its own power. It is dependant on global forces beyond the mound of clay we call a nation and dependant on the collective effort of the citizens—together with all that they believe in and strive for, create and destroy—that make a nation a nation.

That’s why I’m not inclined to make blanket denunciations (or canonisations) of governments, be they led by the likes of John Howard or Kevin Rudd. For instance, blaming the Howard Government, holus-bolus, for the disconnection of our democracy may be a partial truth, but it is too neat and too easy to be an absolute truth. It may keep Howard haters warm at night to howl at the moon about the sins, real and imagined, of the former Prime Minister and his minions, but it does little to advance the cause of progressive politics beyond the converted.

Don’t get me wrong, I am no fan of John Howard. I was frequently astounded by his Government’s brazen contempt for democratic principles, but publicly demonising neo-conservatives does not engage the broader community.

One of the lessons to be learned from the Coalition’s 2001 and 2004 Federal Election victories is that a majority of the electorate are more interested in the backyard cricket of their families and local communities than the Test match in the colosseum of Canberra. It seemed that as though, so long as Australia’s unprecedented economic boom continues and real estate prices remain buoyant, the Howard Government in general, and the Prime Minister in particular, had the tacit approval of a majority of voters to do whatever they pleased, within reason. For example, 72 percent of Australians aware of the Cole inquiry into the Australian Wool Board scandal believed that, despite the denials of Howard and his Cabinet colleagues, the Government knew of the kickbacks; and, in the lead up to the 2004 Federal Election, 51 percent of Australians thought Howard had been dishonest about the children overboard affair[iv]. As John Stirton, of ACNielson, commented, ‘people expect politicians to behave like politicians and so are prepared to forgive the PM as long as he is seen to deliver.’[v]

And there’s the rub. The past fifteen years of economic prosperity—a prosperity largely based in the economic reforms of the Hawke and Keating Governments—was perceived by many voters as Howard’s achievement. Howard was seen to have delivered. And that perception helped lull us to sleep—inducing a national narcolepsy on matters of public importance, such as climate change and the skills shortage, and matters of public morality, such as Reconciliation and the AWB scandal.

This phenomenon is not new.

Writing in 1909, William Guthrie Spence[vi]—a founder of the Australian Workers’ Union and the Australian Labor Party, and a pro-conscription Labor rat to boot—had this to say about his fellow Australians:

‘The wage slave who is not an active member of a Labor League or affiliated Union is so mentally lazy that he either takes his cue from his boss or the press. He never attends a meeting of any kind, and sometimes does not know the difference between a State and Federal election. He can talk sport, but never reads a book on any intelligent subject, and never does any thinking. There are thousands in the big cities whom this description will fit, and it is not easy to reach them. They are conservative by instinct. Some of them are in Trade Unions, but do little beyond grumbling if the officers fail to secure advantages for them. About the only thing to wake them up a bit is to be out of employment. It gets into their thick skulls then that the existing order of things is not exactly going right.’[vii]

A century down the track, Spence’s stinging critique still has currency.

Sport remains our abiding national obsession—as the author of The Longest Decade, George Megalogenis, has said, ‘Australians arguably waste more intellectual energy on sport than any other people’[viii] – and we remain conservative by instinct when it comes to changing governments.

To sum up, Australians just don’t, to be blunt, give a rat’s arse about politics. And why should they? After all, if pollies are, as the Australian Democrats’ founder, Don Chipp, used to say, bastards who need to be kept honest, why bother?

Why? is a question I am asked occasionally by friends and relatives, and often by acquaintances. Why work as a speechwriter? Why work in politics? Why the Australian Labor Party?

Why not? is the abbreviation of my response.

I believe the why questions say two things about my inquisitors.

Number one: They are—in a drive-slowly-past-the-car-wreck kind of way—drawn to politics. It appals, yet compels.

Number two: Although they are drawn to politics, they often find it difficult to make sense of the wreckage.

For instance, Australia’s other ‘great race’, the annual Bathurst 1000, was run on the legendary Mount Panorama circuit on October 10, 2004—the day after the Howard Government’s fourth and final Federal Election win. I’ve never been to Mount Panorama, but, having grown up in the backseat of two Valiant Chargers, retain more than a passing interest in the day-long telecast.

That Bathurst Sunday fell on the birthday of a nephew. Consequently, I found myself corralled with the other males in an outer suburban backyard, drinking Victoria Bitter and watching the V8s climb up and down the mountain on a TV plonked on the back lawn, while the kids and dogs ran around and the females congregated inside. (For the record, 2004 was the year Holden’s Greg Murphy and Rick Kelly won after Jim Richards’ V8 hit a kangaroo at 190 kilometres an hour.)

The newsprint on the ALP’s defeat was barely dry, but politics was not mentioned until the closing stages of the ‘great race’. One of my relatives—a skilled tradesman who works hard, makes a good living, and would probably be ear-tagged as ‘aspirational’ before being released back into the suburban wild by a pollster—pulled up to my elbow and asked whether I’d lose my job because of the election loss.

‘No,’ I said, and reminded him, ‘I don’t work in Canberra. I work in State politics.’

Nodding assiduously, my relative considered what I’d said for a moment before proffering his judgement of the not-so-great-race for the Lodge: ‘Ah, well. I reckon it’s good Howard beat the other bloke. Our interest rates won’t go up now.’

To signal that our discussion had ended, my relly then moved closer to the telly. That bloke’s partner later complained to me about the unfairness of the Howard Government’s industrial relations laws. And, as we all know, interest rates did rise.

Love it or loath it, Bathurst is a reality in Australia. People watch it, year in, year out. People want to see the Australian-made car win. And, invariably, the Aussie car does win. Some people are Holden people. Some people are Ford people. Some barrack for their favourite driver. Some watch what’s on the other channel. Few of the spectators are intimate with the mechanics of a Commodore or a Falcon, but most would be more likely to name the driver who won the most Bathursts in the 1970s (the late Peter Brock) than that decade’s longest serving Prime Minister (Malcolm Fraser).

This does not mean Spence was correct when he accused Australians of being ‘mentally lazy’ souls who ‘never’ think.

Australians do think.

It is just that, generally speaking, we don’t think very much, or very often, about politics. Australian democracy is still strong by world standards. Our brand of representative government compares well in terms of its inclusiveness, longevity, and innovation. For example, more than 94 percent[ix] of the electorate voted during Australia’s 2007 Federal Election, compared to around 61 percent[x] of the voting age population during the United States’ 2004 Presidential Election.

Australian democracy does not need systemic change. We do not need, for instance, to follow California’s road to neo-populism and introduce voter propositions, which have proven disastrous for sustainable economic and social policies[xi]. What Australia does need is greater participation from the community, and greater protection of Federation’s democratic principles.

Having lived in the U.S. from 1995 to 2001, and covered part of the 2000 Presidential Campaign, I am firmly of the view that U.S. democracy is inferior to the Australian brand; that U.S. democracy, like Tom Cruise, is a product best viewed on the big screen.

The 2000 Presidential Campaign—notorious for the hanging chads, butterfly ballots and Supreme Court battle that raged around the 537-vote winning margin in the deciding State of Florida—is a case in point. Many of the Democrat supporters I knew in the run up to the 2000 election were asleep at the wheel. They did not like the then-Texan Governor, George W. Bush, but nor did they like the then-Vice President, Al Gore. More than a few told me they didn’t see any real difference between Bush and Gore—or Republican and Democrat—so they either did not vote or voted for the Green presidential candidate, Ralph Nader. That split of the Democrat vote—it should be noted that the U.S. President is not elected by preferential or popular vote (if it had been, Gore would have won)—was critical to Bush’s 2000 victory, much the same as Ross Perot’s splitting of the Republican helped tip the balance for the Bill Clinton-led Democracts in 1992.

Too many people thought it did not matter who was leading the United States. As a result, Bush won by 537 votes, and was in the Oval Office on 9/11. I’m not one for hypotheticals, but I suspect Gore would have handled the war against terrorism—not to mention other global issues such as the Kyoto protocol and the unravelling of Wall Street—quite differently to Bush.

As I said earlier, Australian democracy compares favourably with most international alternatives. For instance, our Federation has been running for 107 years and counting – surviving two World Wars and Sir John Kerr’s dismissal of the Whitlam Government in 1975. Not only that, one of the universal safeguards of democratic elections—the secret ballot—was invented in Victoria in 1856.[xii] But the continuity and relative strength of our democracy does not entitle us to feel self-satisfied, because it could, and should, be much better.

As Paul Keating’s former speechwriter, Don Watson, has written: ‘Politics is played on a narrower field and one where inspiration and independent thought are not encouraged. The field is defined by ideological think tanks and players are professionals who work to a game plan or strategy.’[xiii]

As an aside, Watson’s Death Sentence, in what read to me like a form of penance for his years of political servitude, goes on to say that speechwriters in Australia are mostly required for jokes, sporting analogies, and copy editing.

That has not been my experience.

My one meeting with Graham Freudenberg, the speechwriter for former Prime Minister Gough Whitlam, was more illuminating. Freudenberg’s golden rule, he told me, was to find out what kind of audience he was writing a speech for, find out what that audience was expecting and tailor the speech accordingly. The beauty of Freudenberg’s approach—an approach that goes to the heart of good politics, in my book—is that it focuses primarily on engaging the public: find out what people want to talk about and talk about it.

In other words, engage people.

That’s what Kevin Rudd did in the run up to the 2007 Federal Election. That’s what John Howard did not do. That’s why Rudd won.

Politics is, in that way, straight forward. It’s all about implementing a three-step plan for a more engaged democracy: find out about it, listen about it, and talk about it.

And what is it?

Simple. Good ideas.

The kind of ideas that will make us a better nation. The kind of ideas that are not the domain of Canberra’s Capital Hill—and never have been—as Spence rightly pointed out back in 1909:

‘The great and important difference between the Liberal Party and the Labor Party of today lies in the fact that the Liberal policy and platform were and are made by politicians. … Reform is initiated by the people in the case of Labor, but is kept in the control of politicians in the case of the Liberal Party.’[xiv]

The surest way to engage the Australian people is to pay heed to Spence’s words—to work up policies that are informed by the everyday needs of working Australians. I am not talking about poll-driven policies. Nor am I talking about buzz phrases like ‘middle Australia’ or ‘working families’. I am talking about finding ways to make the things that matter most to our nation—such as whether or not we will have enough water or fuel in 25 years—matter to the people of our nation.

This is not the safe route. It is not the quiet route. It is loud, risky, roudy, and requires political cojones. It is, in effect, exactly what a democracy is supposed to be about: debating, arguing, and cajoling each other until we come to a broad consensus on issues of national importance. It is the antithesis of the kind of snake-charm politics that John Howard regularly performed on talk radio, and it requires an affirmative response to the rhetorical question Paul Keating has asked:

Is politics about those kind of things [meaning changing the nation for the better] or is it simply a sort of survival art form where you do the tricky-poo changes your Party tells you, ‘Look we’ve done our focus groups this week, you better not talk about that, you better say this and you better say that’? Well, I couldn’t put up with one minute of that, you know.[xv]

There is, in other words, nothing wrong with having an idea. Original thought is nothing to be scared of. Original thought does not necessarily reside in a focus group, nor have to be imported, via some third way, from Britain or the United States.

We need to trust our own ability, and appeal to the better angels of the Australian character. As Spence wrote, ‘the Labor Movement is based upon a recognition of the right of the people to govern themselves in their own way and according to their own ideas.’[xvi]

Engagement is what real democracy is about. Engagement is what is required.

Democracy works best—and by best I don’t mean most efficient or smoothest—when it attracts a critical mass of community involvement. The truth is, we have retreated from our communities and are living, more and more, in the backyards of our suburban mansions. The problems we face appear either too distant or too overwhelming for us to tackle as individuals. And, most importantly, we are no longer a single-minded, homogenous Federation. We are, instead, a multifaceted suburban sprawl of a nation divided by region, by religion, by income, by interest, by age, and by ethnicity.

That is not necessarily a criticism.

Our multifaceted culture can and should be a national asset—so long as our democracy avoids clichéd populism and reflects the diversity of views and backgrounds held by the population it represents. Our multifaceted present can and should be a national asset because it offers us a unique chance to reclaim our multifaceted past.

We are now closer to the nation we were in the Gold Rush than the nation we were in the gold rush of the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne. Back in 1856, thanks to the demographic Big Bang otherwise known as the Gold Rush, Australia was much more multicultural than it would be 100 years later—one-in-five men in the Colony of Victoria, for example, were Chinese. The trouble was that, back then, we lost our nerve and baulked at the chance to become a more inclusive and innovative nation in the decades running up to Federation—non-English speaking schools were drummed out of business, Indigenous Australians marginalised, non-white Australians discriminated against and deported, until, finally, with the passage of the White Australia policy, we were homogenised into two warring tribes, Catholic and Protestant. Half a century of multicultural migration has given us a second chance to discover what kind of nation we can become if we hold our nerve.

As the Cronulla riots of 2005 demonstrated, though, there is no guarantee we will do better than we did in the run-up to 1901.

Part of that reason relates back to the temper of our times. A temper encapsulated by American poet Tony Hoagland during a recent essay on the obliquity, fracture, and discontinuity he associated with language poetry[xvii] (and could equally be associated with the current obliquity, fracture, and discontinuity of Australian democracy):

‘We have yielded so much authority to so many agencies, in so many directions, that we are nauseous. When we go to a doctor we entrust ourselves to his or her care blindly. When we see bombs falling on television, we assume someone else is supervising. We allow ‘experts’ and ‘leaders’ to make decisions for us because we already possess more data than we can manage and, at the same time, we are aware that we don’t know enough to make smart choices. Forced by circumstances into this yielding of control, we are deeply anxious about our ignorance and vulnerability. It is no wonder that we have a passive-aggressive, somewhat resentful relation to meaning itself. In this light, the refusal to cooperate with conventions of sense-making seems like – and is – an authentic act of political, even metaphysical protest; the refusal to conform to a grammar of experience which is being debased by all-powerful public systems. …

’But when we push order away, when we celebrate its unattainability, when our only subject matter becomes instability itself, when we consider artful dyslexia and disarrangement as a self-gratifying end in itself, we give away one of [the] most fundamental reasons for existing: the individual power to locate and assert value.’[xviii]

To recap, we are anxious, we are vulnerable, we are ignorant – and we resent it.

This needs to change. We need, as a nation, to start practicing a brand of politics that reflects the culture of our nation at its best. Or, to put it in terms a cricket tragic can fathom, you don’t have to play like Alan Border’s ugly Australians to win the Ashes.

[i] C.L.R. James, Beyond a Boundary, Duke University Press, 1993.

[ii] Ibid, p66.

[iii] Rose Melville’s 2000-02 study of peak body NGOs (Changing Roles for Community-Sector Peak Bodies in a Neo-liberal Policy Environment in Australia, Institute of Social Change and Critical Enquiry, 2003) found that, under the Howard Government, more than 50 per cent had lost significant Commonwealth funding, and 20 per cent had lost all Commonwealth funding. As the University of New South Wales’ Joan Staples has pointed out in her discussion paper, NGOs Out in the Cold (Democratic Audit of Australia, June 2006, http://democratic.audit.anu.edu.au/papers/20060615_staples_ngos.pdf) de-funding was just the beginning of the Howard Government’s war on independent-minded NGOs, with ‘de-funding, forced amalgamations and ‘mainstreaming’ which silences minority voices, purchaser-provider contracts which have NGOs delivering the Government’s agenda, and confidentiality clauses which restrict or forbid NGOs speaking to the media’. According to Staples, this approach, which echoes the Victorian Kennett Government’s attack on NGOs through de-funding in the 1990s, is consistent with the counter-intuitively coined term, ‘public choice theory’: ‘It rejects a pluralist or discursive view of democracy and any role for NGOs in the development of policy.’

[iv] Michelle Grattan, ‘Truth, the first casualty’, The Age, July 19, 2006.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] No contemporary mention of Spence can be made without noting the notorious lines on page 587 of his book, Australia’s Awakening: ‘The Party stands for racial purity and racial efficiency—industrially, mentally, morally, and intellectually. It asks the people to set up a high ideal of national character, and hence it stands strongly against any admixture with the white race. True patriotism should be racial.’ Spence is not alone in his thinking. Many of the founders of Australia’s Federation had similarly repugnant views that are at odds with the multicultural heritage of the Gold Rush and the Eureka Stockade, and are, in my view, part of the rise of a misguided nationalism in the 1890s that confused Australia with the British Empire.

[vii] William Guthrie Spence, Australia’s Awakening, The Worker Trustees, 1909. PP 334-335.

[viii] George Megalogenis, The Longest Decade, Scribe, 2006. P 153.

[ix] Source: Australian Electoral Commission.

[x] Source: United States Election Project, George Mason University.

[xi] For more information read Peter Schrag’s Paradise Lose (University of California Press, 1999) – a cautionary tale on voter propositions, beginning with Proposition 13, which introduced radical tax limits, in 1978.

[xii] The secret ballot was the brainchild of Henry Chapman – the solicitor-cum-Parliamentarian who, coincidentally, defended John Josephs, the African American who, unlike several white U.S. citizens who were at the Eureka Stockade, was abandoned by U.S. authorities and became the first of 13 miners to stand trial for high treason following the rebellion. Josephs was acquitted.[xii]

[xiii] Don Watson, Death Sentence, Knopf, 2003. P 55.

[xiv] William Guthrie Spence, Australia’s Awakening, The Worker Trustees, 1909. P 308.

[xv] George Megalogenis, The Longest Decade, Scribe, 2006. P 152.

[xvi] William Guthrie Spence, Australia’s Awakening, The Worker Trustees, 1909. P 430.

[xvii] Language, or L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E, poetry is almost impossible to define. At its essence, it is concerned with the use of words and poems as objects.

[xviii] Tony Hoagland, ‘Fear of Narrative and the Skittery Poem of Our Moment’, Poetry Magazine, Volume 187, Number 6, March 2006.